By Luiz Carlos Prestes Filho –

Brazilian cinema will be present at IDFA – International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam 2020, one of the most important events in the genre, with the documentary “In My Skin” by Val Gomes and Toni Venturi. The film brings up different situations of racism or, as Val Gomes states: “Racisms that happen in the silence and complicity of daily life that many people “do not see” and that blacks are systematically subjected to.” In an exclusive interview with the newspaper TRIBUNA DA IMPRENSA LIVRE, the authors state:

“We are happy that such a local issue, as the racial dispute in Brazil, has touched the eyes of Europe. At the same time, we understand that the rooted racism in our land is a result of colonial policies from the European powers. They had a lot to do with this history of exploitation and misery.”

Prestes Filho: Did the authors of the movie “Inside My Skin” choose the theme or did the theme choose the authors?

Toni Venturi: The genesis of the project dates back to 2015 when Brazil was immersed in the political crisis, fueled by the anti-corruption wave that took over society. All mixed up with the economic recession and the streets occupied by the white middle class unsatisfied with the inclusion of blacks and the poor at the center of social life that. Later, I came to understand that this movement had the political objective of interrupting the cycle of popular governments. The institutional instability led me to think of a film that reflected the new face of Brazil that was being formed at this moment. However, the research revealed that it was too early to understand the complex social and political moment, that the film would look pretentious and soon be dated. At that time, my production house, Olhar Imaginário, was involved in the shooting of the series “Cena Inquieta” about underground group theater, black and gender experimental theater. The racial theme already permeated my imagination. It was at this point when Val Gomes, a black sociologist and researcher of the series, joined the project to collaborate in the documentary. She introduced me to a new universe of black literature that revealed the importance of the racial issue as a central element of social inequalities in Brazil. This was really revealing. Until then, my intellectual analysis, based on the classic Marxist concept of class, did not see the theme of race as essential in the discussion of our identity and the formation of society. So, we decided to dive together in this field. I am very grateful for this experience because it changed my perception of the country and my relationship with the Brazilian people.

I think the theme chose me, after all I am an Italian descent, privileged by the whitening policies of the beginning of the last century, which needed to wake up to this reality. Better late than never.

Prestes Filho: How did the characters Estefânio Neto, Rosa Rosa, Wellison Freire, Jennifer Andrade, Neon Cunha, Daniela dos Santos and Cleber dos Santos come about?

Prestes Filho: How did the characters Estefânio Neto, Rosa Rosa, Wellison Freire, Jennifer Andrade, Neon Cunha, Daniela dos Santos and Cleber dos Santos come about?

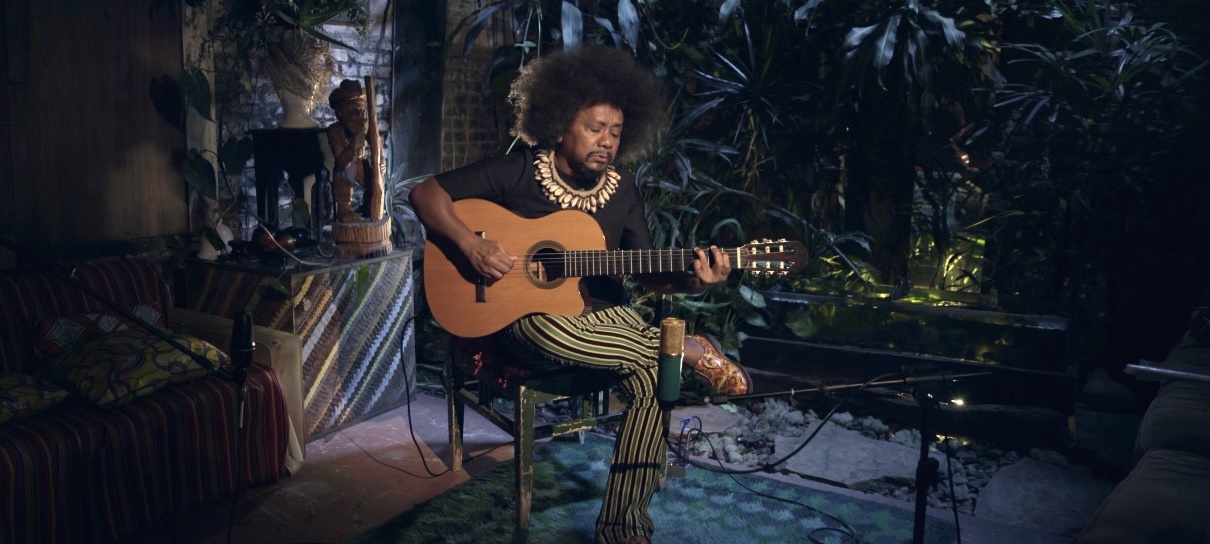

Val Gomes: Initially, Toni and I worked the concept of the cases we wanted to show in the doc. Extreme situations of racism? Or racisms that happen in the silence and complicity of daily life that many people “don’t see”? And that black people are systematically subjected? Normally, white people is touched when there are extreme situations of humiliation, such as the lawyer who was handcuffed at the Forum in 2018. Or when the crowd yells in unison “monkey” to a black player. I wonder if they are really touched or, as Lacanian psychoanalysts would say, they feel pleasure in the humiliation of the other. Anyway, we chose to show a wide range of racism, from the subtle to the explicit ones. We created a network with 9 researchers, mostly from the outskirts, to seek people willing to tell their personal stories. In addition, we attended various seminars and activities, trying to identify possible characters. The researchers worked on a spreadsheet with the data of the character candidate and recorded a video telling his personal story because another essential element for the film is the screen charisma. We took into account social class, education, profession, skin tone, etc. I did the first filter, then I discussed with Toni. It was a process of several months. During the shooting, we recorded 12 “cases”, but in the film only 7 appear, with 9 characters. Five stories were cut in the editing. The strength of the film is in the characters, blacks that we present with all dignity in their day-to-day. In the doc, we have a model and performer artist, a domestic worker, a doctor, a waiter, a teacher, a trans public servant, two college students and a mother who lost her son murdered by the police. They are ordinary labor people that we see every day on the streets, buses, metro, in commercial establishments and a large part of society ignores them.

Hence, when you are facing these people, in a serene and thoughtful situation, and listening to their truth stories they lived in their skin, you cannot escape and start to think that black lives matter.

Prestes Filho: Did the authors choose to give name, identity and address to racism in Brazil?

Prestes Filho: Did the authors choose to give name, identity and address to racism in Brazil?

Toni Venturi: Brazilian rooted racism has its own symbolic characteristics only found here. Out of the 10 million blacks kidnapped from Africa to the Americas, half of this population had Brazil as their destination. The mercantile system of monoculture agricultural cycles – extraction of wood, sugar cane, gold and coffee plantations – in a land of continental dimensions fed on this enormous amount of slave labor. The wheel of capitalism has been grinding people for centuries. There were 350 years of slavery, a history of blood made invisible by the white economic elite, but which is beginning come up. We were also the last country in the Western world to abolish slavery. These infamous deeds point to the concrete need for historical and economic redress for Afro-Brazilians. This is a discussion that we need to have in the next decade, and it has to do with quotas and the granting of privileges. In fact, one of the burning themes of the documentary is the conflicts that happened between the interviewees and myself. From the point of view of cinematographic language, we use the clashes with the white director as a device to generate dramatic tension and bring the viewer’s reflection. Facing the racial issue is not pleasant. And anti-racist whites have to know that there is pain and discomfort on this journey.

But, makes us better human beings.

Prestes Filho: Was the language of the documentary defined by the sponsors? Or exclusively by the authors?

Toni Venturi: The project was produced totally independently. The financing of FSA – ANCINE’s Sectorial Audiovisual Fund covered half the value of the film’s production. The other half comes from sponsors, the agency Spcine from São Paulo and Cultural Institute Çare. These resources did not arrive with any editorial demand either. Once the documentary was finalized, together with the distributor O2 Play we looked for a VOD company and Globoplay got interested. At this point the film was already selected for the 25th It’s All True Film Festival 2020.

Then we started a single negotiation that did not betrayed the film’s anti-racist principles.

Prestes Filho: Today the left and the right attack the media big groups, especially Globo Organizations. In this context, what was it like working to broadcast the documentary on Globoplay?

Prestes Filho: Today the left and the right attack the media big groups, especially Globo Organizations. In this context, what was it like working to broadcast the documentary on Globoplay?

Val Gomes: The audiovisual sector is going through a very difficult moment, the worst of the last two decades: the halt of ANCINE funding, the veto of the president of cultural incentives and a complete absence of structural public policies. All of this added to the pandemic of Covid-19 is leaving us with no horizons. We finished “In My Skin” in March and we were thinking how to launch it with the cinemas closed. With the murder of George Floyd in the US, we saw sectors of Brazilian society interested in embracing anti-racist actions. So, we went after the streaming companies. We contacted Globoplay and they showed an immediate interest and we sew a different negotiation. The film is permeated with an ethical commitment. We presented to Globoplay our fundamental issues and made clear that the publicity campaign had to carry out a truly anti-racist message. Our understanding was that the release could not lose the political meaning that the film carries. This was accomplished. In addition, we implemented an emotional health care service for those who entrusted us with their intimate history, offering psychological support from “AMMA Psy e Negritude Institute”, for the 9 people (characters) who have their stories narrated in the work. And we share 70% of the licensing revenues with 49 people (44 blacks and 5 whites) who made this film.

This was our experience, a mature and firm negotiation at all times.

Prestes Filho: Racism in Brazil has deep roots, it hits blacks, Africans, Indians, Latin Americans and Asians. Do the authors have to look at all aspects of racism? Do you think of new films?

Val Gomes: Yes, there are many forms of racisms. The most known in Brazil is anti-black and against indigenous peoples. In the case of “In My Skin” the focus was the anti-black discrimination. We want to show that there was a secular political project aiming the exclusion of the black population and designed by governments and white society. I have a project that dialogues with the effects and consequences of rooted racism, a series of documentaries about plastic artists, “Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Art”. Today, we have a significant number of Afro-Brazilian works and artists, with a diversified production and international recognition, which has very little projection in Brazil. The series is curated by anthropologist Hélio Menezes, in which we intend to make a cartography of the current production of plastic arts in the country. A market traditionally occupied by the white elite.

Prestes Filho: How do the authors see current public policies to combat racism in Brazil? The president of the Palmares Foundation has carried out revisionist actions. Which way to go?

Val Gomes: There is a racist project led by the present right wing president and his subordinates (mostly white, but with some blacks, like the president of the Palmares Foundation) that represents the segments of society that are not satisfied with social advances and identity issues. But the history of Brazil and the conquests of the black movement were never linear. Whiteness does not support social advancement, given the reaction against quotas in universities and public tenders, against the regulation of domestic work, and recently the achievement that obliges political parties to proportionally invest funds between white and black postulants. There is always contention and the black movement continues to fight to eradicate these violent patterns of exclusion. We have won many victories over the decades. The fight against racism continues to happen regardless of the federal government and, despite its policies, the black movement has growing. The result of the 2020 municipal elections shows that there has been a significant increase, in several cities, of black women elected councilors. The most voted in the city of São Paulo is a black woman, Erika Hilton. She will be the first black trans woman at the São Paulo City Council. We also elected the “Quilombola Periférico”, a collective with an agenda to combat institutional racism in the city, among other blacks with a progressive agenda. This November 15th election set two records for the quilombola population in electoral processes. The first refers to the number of candidates for mayor and councilor. Approximately 500, according to a survey by the National Coordination for the Coordination of Black Rural Quilombola Communities (CONAQ). The second, 56 representatives of quilombolas were elected: a mayor in Cavalcante (Goias), a vice in Alcântara (Maranhão), and 54 councilors in 10 states.

Is it still too little? Yes, but we blacks continue to fight for a better Brazil for all Brazilians.

Prestes Filho: The black in Brazilian cinema today has directors and directors, men and women screenwriters, actresses and actors, producers and producers. Has there been a breakthrough? What names would you name?

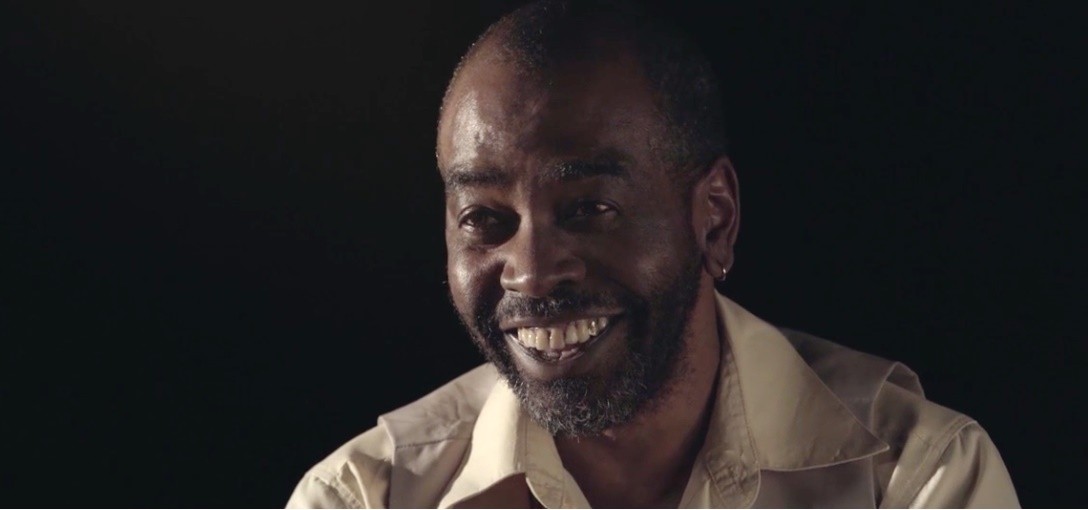

Toni Venturi: There are black filmmakers and professionals – directors, screenwriters and producers who were made invisible due to our racism. But at the moment, they are showing up with all their strength. They are the offspring of the quotas and social inclusion that the country lived under Lula governments and the affirmative policies of the last decade of the Brazilian cinema. Another factor that makes it difficult for black people to enter the audiovisual sector is a subjective element: trust, a fundamental pillar in team building. The mistake in choosing is fatal. Whites, who live in the privileged white bubbles, study in the faculties of whites, will automatically work with other whites thus creating the vicious circle of structural racism. For the production of “In My Skin” we went after black professionals and technicians. The production team is 100% black, with my exception. Today, the house Olhar Imaginário has a department to receive film projects generated by black creators which is coordinated by Val Gomes. We broke this paradigm. There is a group of filmmakers and black creators acting strongly in Brazilian cinema today, such as directors Joelzito Araújo, Adélia Sampaio, Jefferson De, Camila de Moraes, Daniel Fagundes, Renata Martins, Viviane Ferreira, Lázaro Ramos, Renato Cândido, Sabrina Fidalgo, André Novais Oliveira, Yasmin Thayná, Gabriel Martins, Juliana Vicente and many others coming soon.

Prestes Filho: The film “In My Skin” was selected for the IDFA – International Documentary Festival in Amsterdam. What is the expectation?

Toni Venturi and Val Gomes: We are glad that such a local issue, such as the racial dispute in Brazil, has touched the eyes of Europe. At the same time, we understand that rooted racism in Brazil is the result of the colonial policies from the European powers. They were responsible for this story of exploitation and misery. IDFA is one of the most important festivals of its kind and we hope that the screening of the film in the prestigious “Frontlight” section will open the door for the distribution of the documentary on European televisions and markets. We are proud to have our international debut, on November 24th , exactly where the infamous East India Company of the Netherlands controlled the new world trade, including the slave traffic, playing a determining role in colonial genocide.

It is symbolic fact that catches our attention.

LUIZ CARLOS PRESTES FILHO – Cineasta, formado na antiga União Soviética. Especialista em Economia da Cultura e Desenvolvimento Econômico Local, diretor executivo do jornal Tribuna da Imprensa Livre. Coordenou estudos sobre a contribuição da Cultura para o PIB do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (2002) e sobre as cadeias produtivas da Economia da Música (2005) e do Carnaval (2009). É autor do livro “O Maior Espetáculo da Terra – 30 anos do Sambódromo” (2015).

MAZOLA

Related posts

O profissional – por Kleber Leite

Filosofia

Memória – Josué de Castro

Editorias

- Cidades

- Colunistas

- Correspondentes

- Cultura

- Destaques

- DIREITOS HUMANOS

- Economia

- Editorial

- ESPECIAL

- Esportes

- Franquias

- Gastronomia

- Geral

- Internacional

- Justiça

- LGBTQIA+

- Memória

- Opinião

- Política

- Prêmio

- Regulamentação de Jogos

- Sindical

- Tribuna da Nutrição

- TRIBUNA DA REVOLUÇÃO AGRÁRIA

- TRIBUNA DA SAÚDE

- TRIBUNA DAS COMUNIDADES

- TRIBUNA DO MEIO AMBIENTE

- TRIBUNA DO POVO

- TRIBUNA DOS ANIMAIS

- TRIBUNA DOS ESPORTES

- TRIBUNA DOS JUÍZES DEMOCRATAS

- Tribuna na TV

- Turismo